A Closer Look at the al-Awlaki Allegations

A former CIA officer and an author tell me they have doubts.

The Houthi government released a recording from late 2000 or early 2001 revealing former CIA director George Tenet in a state of anxiety begging the former president of Yemen Ali Abdullah Saleh to release a CIA asset who had been jailed in the country over alleged involvement in the bombings of the USS Cole.

The recordings are noteworthy in themselves, even though Tenet refuses to say the name of the suspect in the recording.

They show that even prior to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the CIA had assets penetrating al-Qaeda even though the agency failed to prevent the atrocity.

An intelligence official with the Houthi government told Houthi-run media that the suspect was Anwar al-Awlaki. Because it was the Houthis who uncovered and published this audio, short of confirmation from Tenet himself, I believe they are among the best possible sources to say who exactly Tenet was actually trying to have set free.

However, I am still working to determine beyond reasonable doubt who was being discussed. While there are reasons to suspect Awlaki, many experts on the subject say the allegation by Major General Abdul Qadir al-Shami, the deputy-head of the Yemeni Security and Intelligence Service, are unlikely.

I spoke with John Kiriakou, a former CIA officer who led the raid against terror suspect Abu Zubaydah in Pakistan and was a case officer in Yemen prior to him leaving the agency and blowing the whistle on CIA torture. Kiriakou doubts the Major General al-Shami’s allegation that Anwar al-Awlaki was the subject of Tenet’s call to Yemen’s president at the time.

Scott Shane, a former New York Times terrorism reporter who has authored a book on al-Awlaki, also has serious reservations.

Shane told me that al-Awlaki was “busy” in 2001, the year that the Houthi government told me the call took place.

It should be noted that in my research I found no other sources claiming that al-Awlaki was in prison in Yemen that year, though he would later be arrested on allegations of trying to kidnap a Shia teenager and a U.S. military attaché with al-Qaeda in 2006.

Shane noted that al-Awlaki was “working on a PhD at George Washington U and serving as imam at Dar al-Hijrah in Falls Church, Va., with a wife and small children at home. He was also, in my opinion, not involved with al-Qaeda [at that time]; he was a conservative but mainstream preacher who would soon preach at the US Capitol and become quite famous after 9/11 for media appearances explaining Islam.”

Shane continued: "I don't think there was any chance that Awlaki was part of Al-Qaeda in early 2001, when he went on hajj; he gradually changed his views 2001-2006; I think he first made contact with Al-Qaeda guys in prison in Yemen 2006-7; by 2008 he had emerged as the leading English-lanuage spokesman for Al-Qaeda; by 2009 he was actively organizing terrorist attacks."

"My own view, based on talking to family and others who knew him well, is that while he was probably exposed to and intrigued by radical views, he only gradually came to embrace them after 9/11, and largely after he left the US for the UK in 2002 and then for Yemen," Shane added.

As I note in my article, al-Awlaki is an incredibly enigmatic figure who is extraordinarily difficult to pin down.

Shane went on to note that Awlaki traveled on Hajj with a colleague from the Falls Church mosque I talked about in my article. That colleague previously told Shane about the trip, and in Shane’s view, “certainly would have mentioned if Anwar had skipped off to Yemen and gotten himself jailed!”

“In those pre-9/11 days, there's no reason for the Yemenis to have arrested him,” Shane told me.

In my previous article, I cited some of the work of Paul Sperry, a conservative journalist with what appears to be a strong bias against Islam. I relied entirely on law enforcement documents he exclusively obtained which pertained to al-Awlaki. Here is what Sperry has reported on that trip for the Hajj in 2001:

Sperry says that he interviewed a man, Hale Smith, who went on that same trip and roomed with al-Awlaki. He writes that Smith told him that al-Awaki “voiced support for terrorism during the Hajj trip.” Smith reportedly told Sperry that he tried to contact the FBI about Awlaki but that they neither took down his name nor telephone number.

Scott Shane’s book tells a different story. Hale Smith apparently told Shane that al-Awlaki was “very Americanized” and provided a “welcome[d] contrast” from the “medieval thinking” of some of the Saudi clerics they had met.

Shane's book notes that Smith provided him with travel documents around the Hajj trip. I asked him whether those documents say if al-Awlaki returned to the U.S. with Smith and the rest of the group. This is vital because Tenet said that the imprisonment of the unnamed individual must end after 50 days. If al-Awlaki returned to the U.S. with Smith, it is essentially impossible that al-Awlaki went to prison in Yemen at that time.

Shane said he does not have access to the documents because he is traveling. He tells me he will search for them when he returns. However, Shane says it is highly unlikely that the documents say whether al-Awlaki returned with Smith and the others on the trip.

I attempted to contact Smith myself, using the phone number provided by the California Bar Association since Smith is cited as a lawyer by both Sperry and Shane. However the person who answered my phone call said there is no Hale Smith there.

Sperry claims the travel agency that booked Smith’s trip with al-Awlaki is located in the same building as the World Muslim League which Sperry calls a “suspected charity front for al-Qaeda.” The New York Times notes, citing documents from the Treasury Department released after a legal battle waged by 9/11 victim families, that one of this Saudi charity’s offshoots supported terrorist organizations beginning in the early 1990s ‘through to at least the first half of 2006.’”

Shane told me he was open to persuasion that he may be wrong. “Say Anwar decides to take a couple days after the Hajj to visit family and gets locked up for some reason. But: he couldn't have been held long; he never mentioned it; Tenet would have had no interest in him; Al-Qaeda would not have seen him as an ally. I can't figure out a scenario that makes any sense.”

While I respect Shane’s work, I do not necessarily agree with this assessment or understand why he concludes that Tenet would have no interest in al-Awlaki or why al-Qaeda would not have seen him as an ally. I see no reason to believe that we know everything about al-Awlaki’s life.

Shane added that he finds the Tenet tape “fascinating.”

“My guess is that the CIA had a plant inside or on the fringes of AQAP, and that the Yemenis, trying to lease the furious Americans, rounded up lots of suspects, including the CIA's guy. But it still surprises me Tenet would be so upset about this and forceful. It suggests the CIA's source must have been a very useful guy,” Shane added.

John Kiriakou, the former CIA officer who had held a post in Yemen, holds a somewhat different view of the phone call.

“The conversation between Tenet and Saleh would be a normal, routine conversation if a CIA source were to be arrested abroad,” Kiriakou told me. “This happens. Remember, the job of the CIA, very simply, is to recruit spies to steal secrets. When trying to infiltrate a group like al-Qaeda, a CIA officer must associate with unsavory characters. Sometimes those characters are arrested. The CIA Director (or deputy director, or deputy director for operations) will then ask the host country to release the source. It’s not an unusual event.”

“I don’t think that Tenet and Saleh were talking about Anwar al-Awlaki,” Kiriakou added. “He had a target on his back for so long that word would have leaked out that he was ‘one of ours.’ That never happened.”

Kiriakou is correct that it has not yet been reported that al-Awlaki was a CIA asset. And his familiarity with the agency lends a good deal of credibility to his claim that had al-Awlaki been a CIA asset, somebody at the CIA would have leaked that before now.

It is undeniable that the idea of al-Awlaki having been an asset prior to the September 11th attacks would upend our understanding of one of the most important figures in the so-called War on Terror.

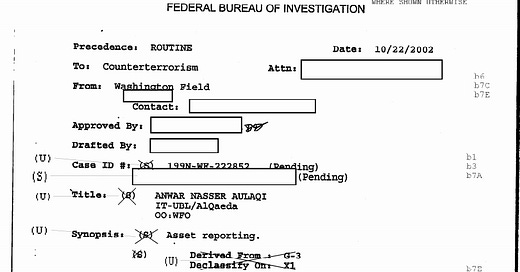

As I noted in my article, there is strong evidence - even an FBI document with his name in the subject field which says “Synopsis: Asset reporting” - showing that he was an FBI asset following the September 11 attacks.

Kiriakou notes that “there’s no evidence that Awlaki was involved in the USS Cole operation,” though he finds it possible that he could have helped recruit talent. “That leads me to believe that Tenet was talking about somebody else.”

As I noted in my article, al-Awlaki was reported to have gone on a “sabbatical” through several countries in 2000. The article that I sourced from was published just 12 days before the USS Cole was bombed. Since al-Awlaki was from Yemen, it’s not unlikely that he went there during that time. I think it is entirely possible that al-Awlaki hooked up with some old Mujahideen buddies from Afghanistan and played a role in the attack on the USS Cole.

Even though al-Awlaki’s involvement has never before been reported, given how poorly U.S. government investigators handled him in the past, I do not believe the U.S. public has been given a full picture of al-Awlaki’s life story and I would not find it surprising if we are still, nearly 20 years after the attacks, learning new information. I also believe, as Scott Shane alluded, that it’s entirely possible that al-Awlaki may have stopped in Yemen in 2001, since he was only one country away during his reported Hajj trip.

In my view, the available timeline does not discredit the Houthis’ allegations. And given the many eyebrow-raising details of al-Awlaki’s relationship to the U.S. government, I believe it was important to profile him for the article.

I will continue to investigate this matter in order to say with certainty who exactly George Tenet called President Ali Abdullah Sale, with such anxiety in his voice, to have released from prison.